External PR incl. Press relations through the ages

Overview

Fig.: Siemens Zeigertelegraf aus dem 19 Jhdt. Foto: Denis Apel. Source: Wikimedia Commons http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.de

Throughout his life, Werner von Siemens paid great attention to the positive image of his company. But first and foremost he saw himself as an inventor who refused to use „Reklame“ (an older German word for advertising) to present his products in a media-effective way. He believed that “really useful things will find their way and recognition anyway”. His products should be characterized by performance and facilitation of everyday life. Nevertheless, Werner von Siemens always knew how to put the services and products of his company in the right light, as long as the measures used for this purpose corresponded to his idea of a serious, public-effective appearance (see Zipfel 1997b, p. 34f.; Kunczik 1997, p. 232).

Even in these early years of the development of public relations, which at that time was still called „Reklame“ or propaganda, Werner von Siemens used a number of means and techniques to inspire every segment of society with his products and to attract financiers. Part of the company’s firm PR repertoire was to combine the effect of presentation with that of cultivating relationships. Siemens implemented this by inviting important representatives from politics and business to present new products.

His career as an officer also enabled Werner von Siemens to establish valuable contacts with the imperial court. These relationships were intended to enhance the prestige of the company, and at the same time Siemens recommended himself as a competent partner in the field of electrotechnical energy. For example, he equipped the Imperial Court with electric lighting for festive balls (cf. Zipfel 1997a, p. 245ff.). Furthermore, the Empress regularly asked him to demonstrate technical innovations at her charity events. In addition, events were held in the empress’s own house at which, among other things, technical innovations in the field of medicine were presented and demonstrated. Siemens invited doctors and other specialists to these events.

To convince the general public of the necessity of his technical achievements and inventions, the company founder installed the first electric street lighting in several streets of Berlin in 1880. Werner von Siemens thus attracted a great deal of public attention and at the same time advertised his products. He described this type of communication as “effect and simultaneous advertising” (Zipfel 1997b, p. 43).

World and trade exhibitions were one of his preferred instruments. These were always conscientiously planned and prepared by Siemens. Within this framework, it was always possible to present exhibits that were of great interest to the public. For example, the first electric elevator at the industrial exhibition held in Mannheim in 1880 transported 8,000 visitors to a viewing platform (see Kunczik 1997, p. 235).

Press relations of Siemens AG from the 1880s to the First World War

Fig.: Elektrisch betriebene Zugmaschine im Berliner Technikmuseum. Foto: LoKiLech. Source: Wikimedia Commons http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.de

Werner von Siemens maintained a critical attitude towards the press throughout his life. Ne-vertheless, press and public relations activities of Siemens could be observed quite early: As early as 1888, a small PR staff was formed around the physicist Willi Howe. This staff collected information on technical and commercial issues, catalogues and publications, and pre-pared suggestions for presentations and speeches to be held by Siemens at the court and in its own rooms. In 1899, the Managing Board decided to intensify press work and hired its own press officer. A “literary bureau” was created, the management of which was transferred to the writer Hans Dominik on October 1, 1900. Dominik had been working for Siemens since April 1, 1900, but left the company again in early summer 1901 (see Kunczik 1997, p. 232 and p. 242ff.; Bentele/Liebert 2005, p. 234).1

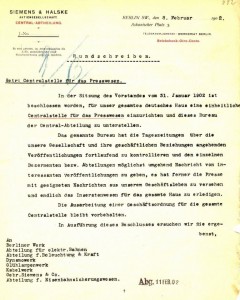

In 1902, a “central office” (Centralstelle) was set up to “concentrate the entire newspaper, advertising and news system” – as a uniform, central literary bureau with special emphasis on press relations.2 On February 8, 1902, a Siemens circular announced:

At the Managing Board’s meeting on January 31, 1902, the decision was adopted to set up a single Central Office for Press Affairs for all our German operations, and to place this bureau under the central department.

(Circular of February 8, 1902, cited after Dittler n.d.)

Such a department, which had to bundle the company’s organizational communications, seemed both appropriate and necessary from the point of view of the Siemens Managing Board at the time. Between the new “Central Office”, headed by E. Neisser, and the “Literary Office”, which had been created two years earlier and continued to exist, a division of labor emerged that assigned the latter a specific and subordinate function:

(…) the collection, processing and forwarding of product-related information and other technical services to the technical and scientific specialist media.

(Dittler n.d.)

In the course of time, press relations intensified – a necessary measure, also in order to withstand the growing competitive pressure. After the restructurings of 1903, Siemens & Halske set up a propaganda office (a common term at the time), which was later renamed Literary Office and, before World War I, Literary Department (see also Kunczik 1997, p. 234).3

External press relations in the changing demands of the 20th century

Over the decades, external press relations have changed considerably, both in terms of organisation and content. While at the beginning of the 20th century, as part of the 1913 reorganization the distinction between central corporate press relations on the one hand and sales-related press relations on the other hand was reconfirmed and continued (cf. Dittler n.d.), the insight that the external presentation of the company must be consistent and that “all communication with publication editors […] must be conducted solely through the Press Bureau […]” (announcement of the company management, quoted after Dittler n.d.) began to gain acceptance as early as the 1920s. Helmut Böttcher, an experienced outside journalist took over managing the bureau in 1922. He also took over the editorship of “Siemens Business Communications” (Siemens Wirtschaftliche Mitteilungen), which had been appearing since 1919. Later there appeared as a follow-up journal the still existing „SiemensWelt“.

This necessity is seen even more strongly after the reconstruction phase of the Federal Republic of Germany, i.e. in the 1960s, when sellers’ markets developed into buyers’ markets. Gerd Tacke, CEO of Siemens AG from 1968 to 1971, is quoted by Dittler, i.e. by the company’s current “Historical Institute”, with the insight “that some day its public relations work would all have to be seamlessly consistent” (quoted after Dittler n.d.). The foundation of a “Central Information Office” (ZI) was the organizational answer to this insight. The ZI is the first “central contact and information point to provide media representatives and interested parties from the general public with product-related, technical and economic information about the company as a whole” (Dittler n.d.).

Outlook on communicative changes at the beginning of the 21st century

Since the 2000s, the digitalization of social communication and the associated changes in the structure and formation of the public sphere have led to a situation in which major changes in corporate communication have been and continue to be observed. In the course of focusing and integrating corporate communications more closely, this also includes the organizational abolition of the separation of external and internal communications (see Santen 2015) and the development of newsrooms since around 2015.

At Siemens, this development was accompanied by a thematic focus, individualization and an increase in the speed of corporate communications, while at the same time greater flexibility (the agile communications department in a more agile company). Clarissa Haller, the current head of Siemens Communications, highlights in 2019 as the strongest change in the Siemens Newsroom in recent years a greater diversity and a higher internationalization of Siemens corporate communications. At the same time, the development of instruments (e.g., “Trello” as a tool) will lead to better and more flexible use of such instruments in strategic planning, but also in controlling. “Real-time controlling” could be the keyword here. Cf. Haller 2019.

Annotations

1 Hans Dominik (1872-1945) combined knowledge of electrical engineering (he had studied electrical and mechanical engineering) and, as a writer, the ability to express technical facts in a comprehensible and popular, “literary” way. Dominik worked for several electrical companies during his life, from April 1, 1900 for Siemens & Halske. However, Dominik soon preferred to work as a freelance writer of technical and utopian novels, from which he continued to commission work for electrical companies (Kunczik 1997, p. 243f.; Bieler 2010, p. 215). A short biography of Hans Dominik at: http://www.mdr.de/geschichte-mitteldeutschlands/reise/personen/artikel12284.html

2 On this organizational solution, see also Bieler 2010, pp. 215f. and 219f. There it is quoted from the minutes of the board of directors. Cf. also Dittler (n.d.).